NASA Mission To Jupiter’s Europa Gets Go-Ahead

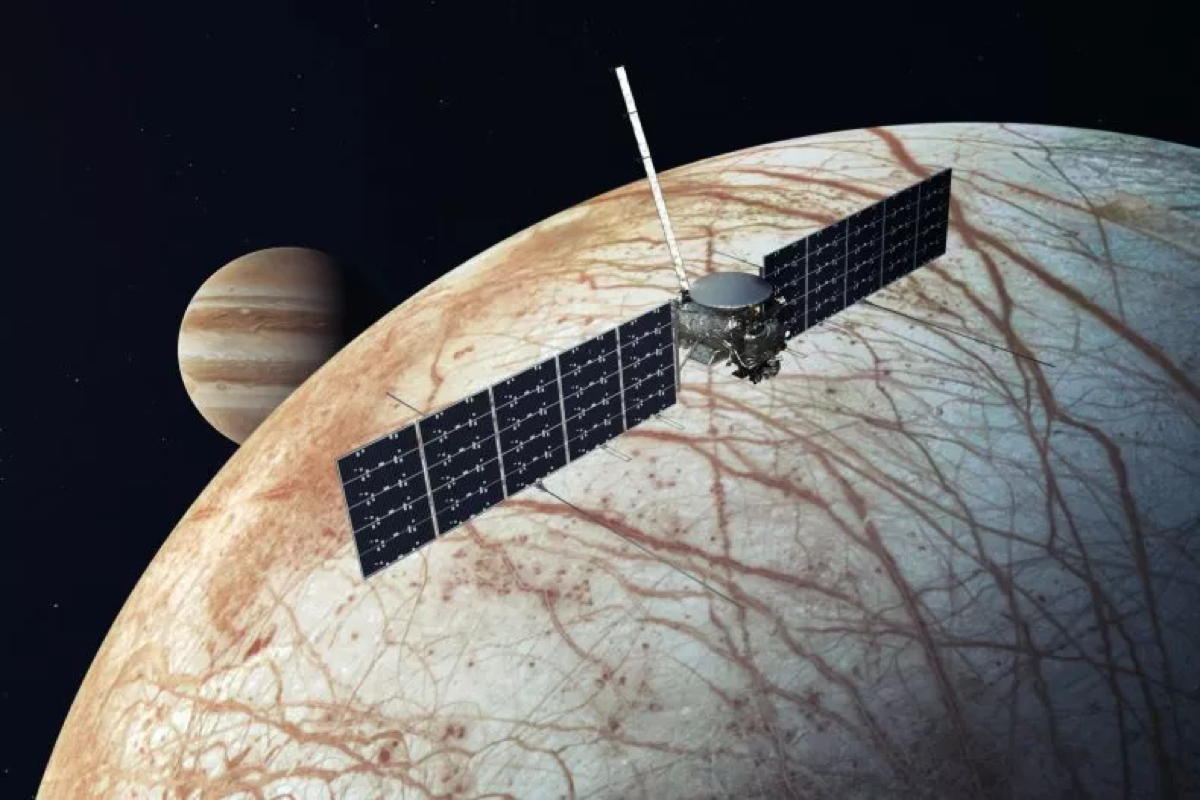

NASA to launch ‘Europa Clipper’ mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa next month as it seeks evidence of life in ocean below icy crust

NASA’s long-planned mission to Europa is set to go ahead next month after engineers resolved a potential issue with Infineon transistors built into the $5 billion (£3.8bn) Europa Clipper spacecraft.

“We are confident that our beautiful spacecraft and capable team are ready for launch operations and our full science mission at Europa,” NASA Jet Propulsion Laborator (JPL) director Laurie Leshin told reporters.

Europa Clipper is the biggest spacecraft NASA has ever built for a planetary mission, weighing more than 3.2 tonnes with a height of 5 metres and a width of more than 30 metres with its solar panels deployed.

Last week the mission passed a critical point known as “key decision point E”, or KDPE, the final review clearing it for a launch window that opens on 10 October.

Interplanetary voyage

If its launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket is successful, Europa Clipper is set to arrive into the Jupiter planetary system in April 2030, where its nine instruments are to analyse Europa’s icy crust and attempt to confirm whether, as suspected, an ocean lies beneath the surface that could support life.

Previous missions suggested Europa could have a suberranean ocean with more than twice the volume of water in Earth’s oceans, while the moon’s fissured surface hints at an active geology that could mean a warm and dynamic environment below.

Europa Clipper programme scientist Curt Niebur said that while it is “extremely difficult to be able to detect life, especially from orbit”, the mission will attempt to confirm whether the “proper ingredients” are present for life to exist.

After proceeding through the planning process for years, US lawmakers permitted Europa Clipper to launch aboard the SpaceX launch system.

But in May NASA engineers detected that Infineon MOSFETS transistors already installed in the spacecraft might not be able to withstand the intense radiation environment around Jupiter.

‘Very harsh’

Europa Clipper is set to fly past Europa 49 times, coming as close as 25 kilometres, meaning it will fly repeatedly through Jupiter’s magnetic field, which is 20,000 times more powerful than that of Earth.

“Jupiter is a very harsh radiation environment,” Joey Mukherjee, a data scientist and software angineer from Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio, Texas who worked on Europa Clipper, said in an interview.

After four months of intensive testing, NASA determined the transistors would be able to perform as expected as they would need to endure Jupiter’s radiation for only one out of every 21 days.

The rest of the time the transistors could partially self-heal by being slightly heated in an annealing process.

“Once it comes out, it comes out long enough for those transistors the opportunity to heal and partially recover between flybys,” said JPL Europa Clipper project manager Jordan Evans.

“This was a huge lift, and I think ‘huge lift’ is a huge understatement,” said JPL’s Leshin.

SwRI’s Mukherjee helped build a system to sift through data collected by the probe’s Ultraviolet Spectrograph Instrument to prioritise what to send back to Earth.

Only a relatively tiny amount of data collected by the mission can ever make it into scientsts’ hands, meaning such data triage processes are critical, said Mukherjee, who also worked on Europa Clipper’s predecessor Juno, which launched in 2011 and has been exploring Jupiter since 2016.

Geysers

During Europa Clipper’s flybys the spacecraft will use another instrument called MASPEX, also developed at SwRI, to try to sniff particles emitted from the moon in huge geysers.

In November 2019 NASA scientists for the first time identified water in the geyser plumes after scritinising it through one of the biggest telescopes in Hawaii.

Europa Clipper will go a step further by detecting particles from the geyser with high fidelity at close proximity to Europa.

After the mission is over, NASA is considering using it to generate more scientific information by crashing the probe into Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, an event which would be observed by the Juice (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) mission launched by the European Space Agency (ESA) last year and due to arrive at the gas giant in 2031.

Mukherjee modelled a simulation of how the crash could appear from Juice’s point of view but said that no final decision has been made about the probe’s fate.