The UK’s top secret listening agency, GCHQ, the successor to Bletchley Park, has released previously unseen photos of Colossus.

The GCHQ announcement celebrated 80 years of Colossus, the code-breaking computer that played such a pivotal role in World War 2 (WW2).

Colossus is said to be the world’s first programmable digital computer, after it was constructed at Bletchley Park, the home of the UK’s second world war codebreakers and a location therefore widely seen as the birthplace of modern computing.

Image credit GCHQ

Colossus computer

“Today we have released a series of rare and never-before-seen images of Colossus, in celebration of the 80th anniversary of the code-breaking computer that played a pivotal role in the Second World War effort,” said the UK intelligence agency.

The Colossus computer was created during WW2 in order to decipher critical messages between the most senior German Generals in occupied Europe. However its existence was only revealed in the early 2000s after six decades of secrecy.

By the end of the WW2, 10 of the machines were in operation in the UK and had been used to decrypt 63 million characters of German messages.

Colossus stood over two metres tall, used 2,500 valves, and was built by Tommy Flowers, the son of a bricklayer who worked for the General Post Office’s telecoms division (later to become BT) at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich.

Image credit unknown

The machine actually measured 7ft high by 17ft wide and 11ft deep, and weighed five tonnes.

It used 8kW of power and incorporated parts from telephone exchanges including 2,500 valves, about 100 logic gates and 10,000 resistors, connected by 7km of wiring.

It could read an estimated 5,000 characters per second, meaning it could take only about four hours to find the first key in a code. As a result Colossus is thought to have substantially shortened the duration of the second world war.

A working Colossus replica on display at the National Museum of Computing was reconstructed by Tony Sale, the museum’s co-founder, based on eight photographs of the machine taken in 1945 and a few surviving circuit diagrams.

![]()

Unseen photos

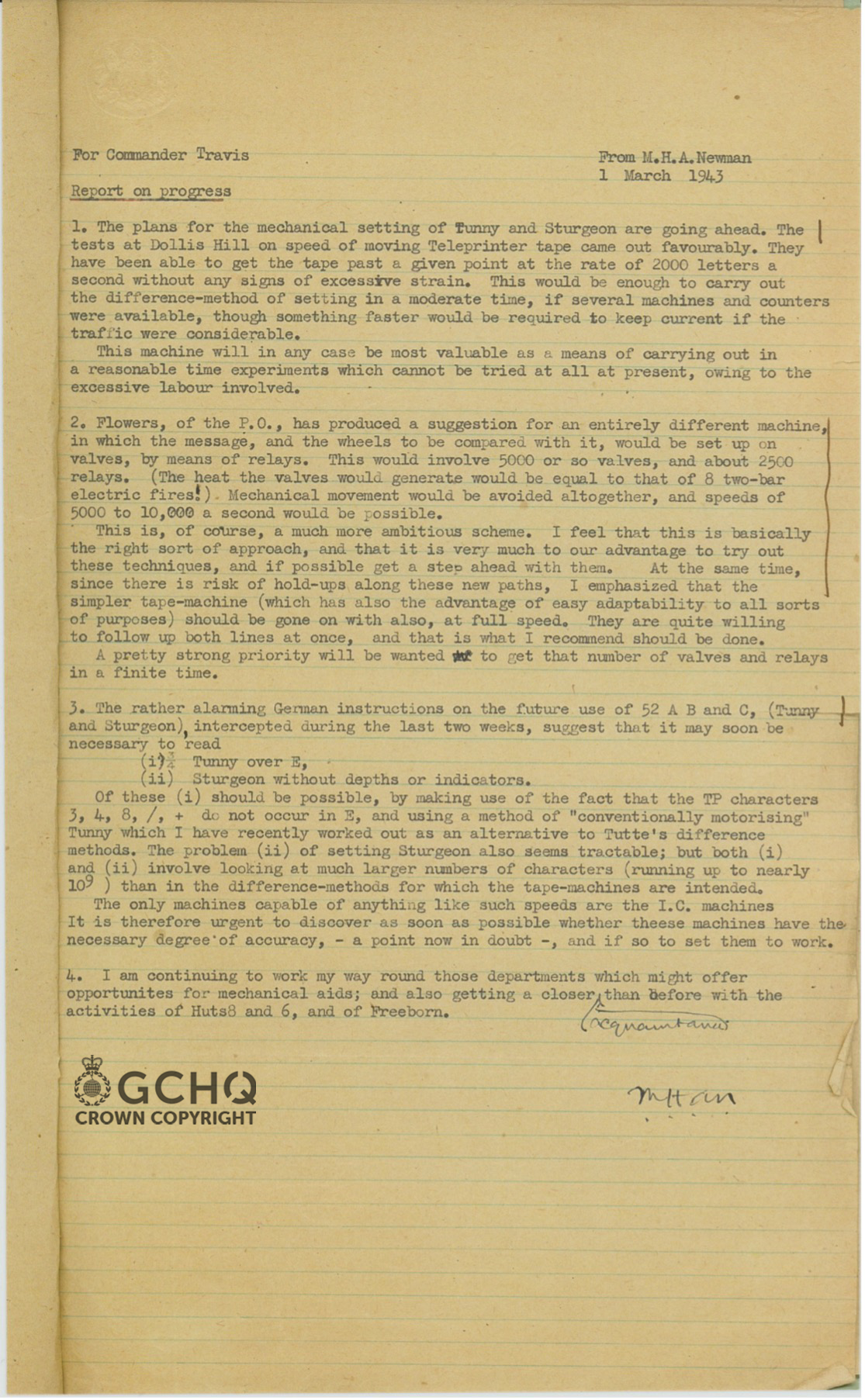

One rare photograph released this week by GCHQ features a letter tracking the progress of the work being done to decipher communications between senior Nazis.

The letter includes the words “Flowers of the P.O. has produced a suggestion for an entirely different machine” – a reference to famed codebreaker Tommy Flowers’ idea that would ultimately result in Colossus.

Another part of the letter reveals the high-level communications Colossus was intercepting, including, “rather alarming German instructions.”

“Technological innovation has always been at the centre of our work here at GCHQ, and Colossus is a perfect example of how our staff keep us at the forefront of new technology – even when we can’t talk about it,” said Anne Keast-Butler, Director GCHQ.

“The creativity, ingenuity and dedication shown by Tommy Flowers and his team to keep the country safe were as crucial to GCHQ then as today,” said Keast-Butler. I’m thrilled to be celebrating the 80th anniversary of this computer and honouring those who worked on it.

GCHQ noted that the engineers and codebreakers who had worked on Colossus were sworn to secrecy and unlike the well-known Bombe Machine, which broke the Enigma cipher, existence of this vital piece of machinery was kept from the history books for almost six decades.

National security

After the Second World War eight out of the ten machines were destroyed and Flowers was ordered to hand over all documentation on the Colossus build to GCHQ. This was partly because the technology was so effective, its functionality was still in use by us until the early 1960s.

“I worked as an engineer on Colossus for a year during the 1960s,” said Bill Marshall, Former GCHQ engineer. “I had just signed the Official Secrets Act and knew nothing about GCHQ but was offered ‘interesting work’ which I believed would be dealing with telegrams for a government department.”

“I was told very little about the machine I was working on – what the machine was actually doing was not for me to know,” said Marshall. “My job was to repair it as necessary, using just a few circuit diagrams and no detailed user handbook. It wasn’t until much later that I found out that the several of the systems and detailed design information were supposedly destroyed at the end of WWII.”

“I’m very proud to have been involved with Colossus even in just a small way, and we should all be proud of what was achieved in the name of national safety and security,” said Marshall.

“Colossus was perhaps the most important of the wartime code breaking machines because it enabled the Allies to read strategic messages passing between the main German headquarters across Europe,” added Andrew Herbert OBE FREng, Chairman of Trustees at The National Museum of Computing.

“This is one of the many reasons we’re so proud to have a fully working reconstruction of a Colossus code breaking machine on display at The National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park,” said Herbert.

“The development of the Colossus machine was a huge advancement in Bletchley Park’s codebreaking efforts helping the Allies break one of the most complex ciphers of WWII,” said Ian Standen, CEO of Bletchley Park. “Thanks not just to Colossus, but the pioneering post-war computing work of codebreakers like Alan Turing, Max Newman, Donald Michie, and Jack Good, Bletchley Park is considered a birthplace of modern computing.”

Bletchley Park it should be remembered was chosen as the host of the world’s first ever AI Safety Summit last November, that was attended a host of nations, businesses and public figures, including UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, US Vice-President Kamala Harris, European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, as well as Elon Musk and Sam Altman and many others.